PFAS – The Next Big Thing?

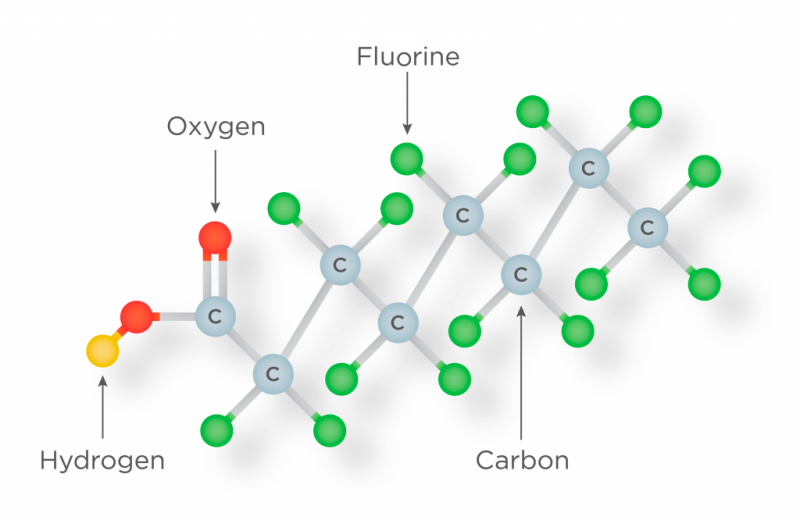

The environmental industry seems to thrive on acronyms and it appears the “next big thing” in our acronym alphabet soup is PFAS. Per- and poly fluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) are a group of manufactured chemicals that have been produced since the 1940s and used in numerous industrial and consumer applications. These chemicals are persistent (i.e. they do not break down in the environment); they bioaccumulate (i.e. concentrations build up over time in the blood and organs); and peer-reviewed studies indicate exposure above certain levels may result in adverse health effects. How big a thing you might ask? Current data compiled by the Environmental Working Group and Northeastern University show PFAS contamination having been identified at 712 locations in 49 states. Michigan currently has the unfortunate distinction of having the most PFAS sites in the nation with 192 sites having been identified by the EWG.

The environmental industry seems to thrive on acronyms and it appears the “next big thing” in our acronym alphabet soup is PFAS. Per- and poly fluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) are a group of manufactured chemicals that have been produced since the 1940s and used in numerous industrial and consumer applications. These chemicals are persistent (i.e. they do not break down in the environment); they bioaccumulate (i.e. concentrations build up over time in the blood and organs); and peer-reviewed studies indicate exposure above certain levels may result in adverse health effects. How big a thing you might ask? Current data compiled by the Environmental Working Group and Northeastern University show PFAS contamination having been identified at 712 locations in 49 states. Michigan currently has the unfortunate distinction of having the most PFAS sites in the nation with 192 sites having been identified by the EWG.

An Emerging Contaminant 75 Years in the Making

Invented in the 1930s and produced commercially in the US and abroad since the 1940s, PFAS compounds are blessed with a number of particularly attractive properties including water repellence, oil and stain resistance, reduced friction, and high temperature resistance, making them useful in all manner of applications. PFAS were seen as miracles of modern chemistry and trade names like Teflon™, Scotchguard™, and Stainmaster® became household words. Perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA) was used for decades to stain proof fabric and carpet, waterproof boots and clothing, greaseproof food packaging like pizza boxes, fast food wrappers and microwave popcorn bags and to make non-stick cookware. Perfluorooctane sulfonic acid (PFOS) was used in aqueous film forming foam (AFFF) firefighting equipment that was commonplace at airports, refineries, chemical plants, and military bases. The metals finishing industries use PFAS compounds in a number of plating operations. Some PFAS chemicals are no longer manufactured in the United States, but PFOA and PFOS continue to be made internationally and can be imported in common consumer items such as carpet, leather, textiles and apparel, paper and packaging, paints and coatings, rubber and plastics. Because these chemicals have been used in an array of consumer products, most people have been exposed to them.

Routes of Exposure

PFAS are manufactured so there are no naturally occurring sources in the environment. The North Carolina Public Health Division reports they can be “found near areas where they are manufactured or where products containing PFAS are often used. PFAS contamination may be in drinking water, food, indoor dust, some consumer products, and workplaces. Most non-worker exposure occurs through drinking contaminated water or eating food that contains PFAS.” Food can be contaminated if impacted soil and/or water were used to grow the food, if food packaging contained PFAS, or if the food was processed with equipment that used PFAS. Drinking water impacts appear to be most commonly associated with proximity to facilities where PFAS were produced or at locations where PFAS were used in the manufacture of other products as well as at locations where AFFF were used in firefighting.

Health Effects

The scientific community’s understanding of environmental and health impacts of these compounds is rapidly evolving. Because they are persistent and bioaccumulate, as people are exposed to different PFAS sources through time, the level of PFAS in their bodies may increase to the point where they suffer from adverse health effects. The United States Environmental Protection Agency (USEPA) has concluded studies that indicate PFOA and PFOS can cause reproductive, developmental, liver, kidney, and immunological effects in laboratory animals. Both PFOA and PFOS have caused tumors in animal studies. The most consistent finding from human epidemiology studies is increased cholesterol levels among exposed populations, with more limited findings related to low infant birth weight, effects on the immune system, cancer, as well as thyroid hormone disruption.

The States Won’t Wait

In 2016, the USEPA issued a lifetime health advisory of 70 parts per trillion (ppt) for two PFAS compounds (PFOA and PFOS) in drinking water. Since then the Agency has held a PFAS Summit in May of 2018 and issued its PFAS Action Plan on February 14, 2019. However, a number of states have expressed frustration with USEPA’s proposed plan and particularly with the anticipated timeline for regulation. Seventeen states have formal policies addressing PFAS and a number of states have taken steps to prohibit PFAS in firefighting foam and food packaging. California and Michigan have established monitoring requirements for water systems and New Jersey has established a maximum contaminant level (MCL) for a PFAS chemical (13 ppt perfluorononanoic acid). It has also proposed MCLs and formal groundwater quality standards of 14 ppt for PFOA and 13 ppt for PFOS. A number of other states including Alaska, California, Minnesota, New Hampshire, New York and Vermont have policies or have indicated they are developing policies that will be stricter that the USEPA’s current 70 ppt health advisory for PFOA and PFOS.

Challenges to be Faced

Many states have no regulation with respect to PFAS, whereas others have MCLs well below the USEPA’s current health advisory. Regulatory objectives in the parts per trillion range tax commercial labs’ analytical capabilities and present a very real challenge to field staff who are responsible for collecting samples. PFAS are everywhere. Standard sampling equipment and sample containers may not be PFAS-free. Field personnel need to be thoughtful in their choice of food and clothing (no prepackaged snacks or fast food, and no Gore-Tex™ or similar water-resistant synthetics), eliminate the use of fabric softeners and certain personal care products, and concern themselves with potential contamination from the use of field staples such as sunscreen, insect repellent, and blue ice. Details matter!

Concerns about potential exposure have essentially outstripped the ability of government agencies to establish policy. States impatient with federal progress on the matter have enacted a patchwork of standards and regulations. It is not just the contaminants and regulations that are emerging; testing protocols are emerging as well. The USEPA has proposed a new drinking water test method but methodologies for media other than drinking water are still in development. Carlson can help bring clarity to a confused and confusing situation.